Intolerant actors gain political legitimacy through democratic processes, pushing for agendas that degrade democratic norms.

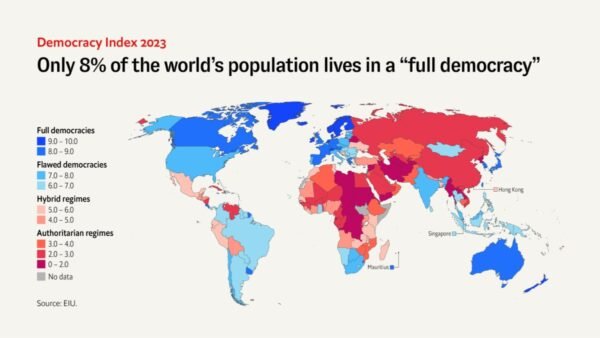

Models of liberal democracy are in decline; the rise of populism has sunk the fiction of liberal democracies, even pushing for agendas that degrade democratic norms. The world is a complex living organism composed of sophisticated systems that establish interactions between human beings and shape our collective consciousness through ways of thinking, ideologies and beliefs. Yet systems do not prevail for eternity; we live in an ever-changing society, where the fiction of a system changes as cultural interactions and values shift. The adoption of democratic models by governments has been happening cyclically, in waves. Still, when the wave goes up (as more states become democratic), it will go down at some point until a new model surpasses or demonstrates better efficiency, and if not better efficiency, a model that society sympathises with.

Faith in liberal democracy boomed at the end of the Cold War after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the democratisation wave in the East. This expanded the Western collective consciousness, which agreed that this model was the best form of government because it maximises individual freedom and adopts liberal economic values. Yet today, this attachment to the liberal democratic model is in decline. There has been rising discontent since this form of government started showing some of its shortcomings. Society demands that under a liberal system everyone should feel included. Yet, each individual part of an organism under a system is unique and different, so ensuring that all beliefs are satisfied is not an easy task. However, with all its imperfections, liberal democracy has proven to be the least harmful system in existence, so why would individuals want to return to systems that have proven to be seriously flawed, and what benefit is there in giving up freedoms to feed the power hunger of political actors?

Latin America is an example of a territory that finds itself in a wave of rising authoritarianism and democratic backsliding; this is due to multiple reasons, but a theory that could explain a rise in a less democratic, and more populist form of government could be by linking the paradox of tolerance with how political actors gain political legitimacy and power.

Why the Paradox of Tolerance?

The paradox of tolerance argues that a society that is tolerant without limit will eventually be taken over by the intolerant. Karl Popper, who developed the theory in the middle of the 20th century, further argues that having a society that possesses unlimited tolerance can lead to social suppression of tolerance itself, as the intolerant groups of society will exploit the freedom and openness to impose intolerant ideas on society. Popper solves this issue with a theoretical framework that suggests that society should reserve the right to suppress intolerance in cases where it undermines or threatens the tolerant framework.

In the context of political systems, let’s suppose that the liberal democratic system is the tolerant actor of the paradox, while the autocratic system is the intolerant. In a democratic setting where individual freedom is maximised, tolerance and political pluralism allow the competitiveness of diverse ideas no matter how extreme they are. Meanwhile, political competition is allowed on a democratic basis, the intolerant, in this case, the non-democratic actor, could use the democratic freedom and processes to gain power and impose non-democratic ideas on society and even the governmental system itself. Causing a process of democratic degradation and a backlash over the core values of democracy in society and within the governmental system. Therefore, in a democratic society where the idea of individual freedom dominates, should it be allowed to tolerate ideologies that seek to dismantle democratic freedom itself?

Historically, in democratic societies, extremist ideas have risen and gained influence sooner or later. In some cases, leaders have used democratic processes to establish themselves in a power position to dismantle core democratic values and restrict freedoms (tolerance in the case of the paradox). Nevertheless, who do we blame if this were to happen? Society for choosing an extremist candidate or the democratic system for allowing the intolerant to gain power?

What if we decided to implement Popper’s solution in this case? Would it be democratic to limit freedom towards ideologies that threaten democratic foundations? Since this infringement on freedom of expression would be against the core values of democracy. Most democratic countries’ political systems have a legal structure and separation of power that safeguards the democratic system through independent and impartial courts. However, not all countries’ democratic systems function with total efficiency and good performance; Inefficiencies caused by Inequality, Social Problems, a weak rule of law and corruption have caused the democratic degradation we have seen in the past twenty years, shifting the preferences of society towards more populist or autocratic systems.

Perhaps if we had inverted the paradox, it could have also explained why authoritarian systems remain in power. The limitation of freedom prevents democratic ideas from gaining power, which is why, through a restrictive framework, they ensure a system where one political idea prevails. The threat of democracy does not exist. Without tolerance, political actors with conflicting ideas cannot exploit tolerance and openness to impose them on society.

Populism is on the Rise.

In general, theories of how non-democratic leaders gain power can be tightly linked with the paradox of tolerance by observing how they exploit democratic mechanisms and processes to dismantle democracy from within. In Latin America, there has been a phenomenon in which populist leaders gain power by presenting themselves as the voice of the people, using an ongoing crisis to empathise with the electoral body. They present themselves as the solution against a corrupt elite or the salvation of a dysfunctional system, and by gaining power through free political competitiveness and the support of society, they advocate for agendas which centralise power, thereby laying the groundwork for the usurpation of power and dismantle the independence of institutions. The theory of democratic backsliding suggests that once the illiberal actor is in power, it may enact incremental autocratization by slowly weakening democratic norms and institutions, the judiciary, the separation of powers and even violating the freedom of expression of journalists and the media.

Steven Levitsky, assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University and Lucan A. Way, academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University, both developed the theory of competitive authoritarianism, which suggests that autocratic-leaning leaders use democratic institutions to gain power. Once in power, they use “areas of contestation” (referring to democratic institutions) but skew them in their favour, resulting in a government that appears democratic by making use of institutions and processes such as elections and at the same time taking advantage of an uneven, non-impartial field that only favours the party in power.

Will Democracy Survive Tolerating Intolerance?

Historically, there have been many cases where autocratic leaders gained power by taking advantage of this weakness of the democratic system, and so have turned democracy upside down through the establishment of an authoritarian system. In the case of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler gained popularity through extremist populist ideas and took advantage of democracy in the country to establish his regime. Hugo Chavez in Venezuela was elected through a democratic process and then, after assuming office, held referendums to amend the constitution, restricting opposition and curbing democratic freedoms. Meanwhile, Erdogan, the current Turkish president, used democratic elections to gain power and after a failed coup d’etat in 2016 pushed forward referendums to amend the constitution, thereby shifting the system from parliamentary to presidential, generating a more autocratic form of government. Ortega, the president of Nicaragua, assumed power through democratic processes, yet he amended the constitution to allow infinite reelection and dismantled democratic institutions. Evo Morales, democratically elected president of Bolivia in 2006, sought constitutional changes to extend his term in office. Only after facing mass protests and allegations of electoral fraud, he resigned office, though his mandate showed shifts and willingness towards a more autocratic government. This continues and to this day,democracy is eroding. Recently, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, president of Mexico until the beginning of October, has been heavily criticised for undermining democratic, independent institutions, reforming the judiciary and executive powers and centralising control over various governmental agencies; concentrating power in his party.

The ultimate question is how to establish a democratic system while ensuring that its operational mechanisms prevent non-democratic actors from coming to power. The problem is that if the main foundations of democracy are liberties and freedoms, limiting them to ensure that the intolerant actor reaches power would be contradictory. At the same time, who sets the definition of an intolerant actor, and to what extent should the actor’s intolerance be socially acceptable?

As challenging as it may sound, crafting a democratic system that prevents authoritarianism without compromising democratic values and principles is possible. The key strategies are establishing strong and independent institutions, educating society with democratic values to prevent uprisings, and ensuring that constitutional safeguards exist. The problem is that democracy is not of the same quality across all regimes, thus explaining why democratic systems will continue down the path of erosion in countries where the level of social discontent is high and the quality of democracy is poor. It is there, where populist actors can sympathise with the people and endanger democratic foundations.

Featured image by IE University Insights, 2022.