What do a $10 pack of 100% recycled toilet paper and a bamboo toothbrush priced like an artisanal coffee have in common? Though they both serve as sustainable alternatives to their single-use or chain-produced counterparts, they also serve as examples of a trend that is hard to ignore: green living often comes with a hefty price tag for the average consumer. This raises the uncomfortable question: has sustainable living become a lifestyle choice for the privileged? Can we realistically build a future within our planetary boundaries when the price of ‘ethically sourced, organic’ bread is too high for the average breadwinner?

In order to attempt to answer these questions, we must first understand what ‘sustainability’ is. We use this notion so often, but it is doubtful if most of us truly comprehend when it is used meaningfully and when as a marketing buzzword. Sustainability is the balance between the environment, equity, and economy. The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development provides the most frequently cited definition: “sustainability is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The term sustainability was first encountered in the 1987 Brundtland Report produced by several states for the United Nations with the aim to identify the effects of human activity on the environment. What is, however, the standard that we can compare our development to in order to validate and quantify how sustainably we are actually developing?

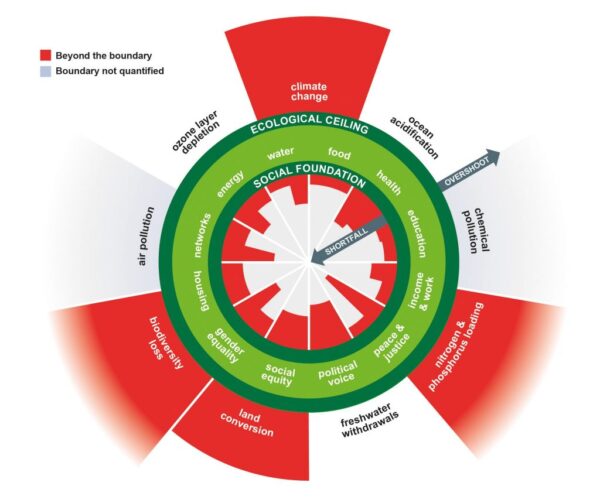

In 2009, Johan Rockström and a group of scientists gave us the answer. They proposed an Earth system framework called the “Planetary Boundaries”. After conducting research that proved time and time again that human activity is indeed the main driver of global environmental change, the group identified nine “planetary life support systems” essential for human survival.Within these systems humanity can continue to operate safely and in harmony with nature. These include climate change, biosphere integrity, and novel entities, meaning the pollution caused by compounds such as plastic. In short: for humans to survive sustainably on Earth, these systems must not be surpassed. If the boundaries are exceeded, there is a surefire risk of “irreversible and abrupt environmental change” which will severely compromise Earth’s habitability. Author Katherine Richardson, professor in biological oceanography and leader of the Sustainability Science Centre in the University of Copenhagen, explained it very well:

“We can think of Earth as a human body and the planetary boundaries as blood pressure. Over 120/80 does not indicate a certain heart attack but it does raise the risk and, therefore, we work to reduce blood pressure.”

Despite the simplicity of the standard, the current condition of the planet is worrying: As of 2023, six out of nine planetary boundaries have been crossed. Only the ozone layer depletion has been reversed. Though exceeded in the 1990s, thanks to global initiatives like the Montreal Protocol, it was soon reversed back into the safe zone. But, scientists nowadays understand that human development, apart from the environmental dimension, is also expressed in terms of a social dimension. Enter the Doughnut. No, unfortunately this is not a Krispy Kreme ad (as much as I would love a classic glazed one right now). Rather, the doughnut is the visualisation of a compass for human prosperity combining a social foundation based on the 12 social principles of the SDG with the ecological ceiling of the aforementioned planetary boundaries. Hence, between these two boundaries a new goal is created: A socially just and ecologically safe space where humanity can thrive.

All of the above is to say that, in theory, the race for sustainable development and sustainability as a lifestyle is a well-known, common goal. But in practice, it sometimes feels like an exclusive club, complete with premium-priced, eco-friendly gear. Zero-waste items, electric cars, and organic fruit all sound fantastic, but their costs frequently seem to be set for those who don’t bat an eye at prices like a $10 smoothie. This disparity in prices raises a significant question: is the environmental movement limited only to people who can afford “luxury lettuce”? Due to their inability to pay more for environmentally friendly options, many families—particularly those in lower income brackets—find themselves with fewer and frequently less sustainable options. We’re asking everyone to go green, yet only a select few can afford the invitation, creating a paradox. The result? Without affordable, accessible options, the average person can feel more alienated from the movement than inspired by it.

There is an undeniable element of privilege embedded in the messaging of sustainable living. The idea that everyone should adopt green consumerism frequently ignores the fact that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to a sustainable lifestyle. While some people are busy comparing the costs of basic foods amid raging inflation, others are shopping at farmers’ markets or trading in their SUVs for electric vehicles.

Privilege is more than just income; it also includes time, education, and access—all of which are necessary for green living. Additionally, companies are increasingly engaged in “greenwashing” their products by charging more for items with earth-tone packaging and leafy logos which might not even uphold the green standards, but only disclose so in the fine print. These methods fall too short of the social basis needed to meet everyone’s basic requirements prior to luxury eco-products becoming the norm, according to Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model. The irony? The current system markets eco-friendly as premium but makes unsustainable choices the default, keeping us all spinning in a cycle of inequality and environmental decline.

Interestingly, younger generations are once again changing this narrative by supporting minimalism as a means of achieving sustainability on social media, particularly through TikTok trends like underconsumption core. Contrary to the upscale, pricey look of eco-branded goods, underconsumption core promotes cutting back on consumption completely by choosing secondhand clothing, reusing objects, and do-it-yourself alternatives to pricey sustainable brands. By promoting sustainability as an attainable lifestyle, underconsumption core illustrates how we might democratise eco-conscious living in simple ways by making it accessible to the everyday basic income consumer. It encourages those with modest incomes to contribute to the movement without breaking the bank.

This trend above all highlights that sustainable living is not about buying bamboo toothbrushes or eating solely organic produce; instead it is about being conscious of our consumption. It is about reusing our things, repairing them, and repurposing those that cannot be mended. But minimalism alone won’t solve the systemic issues driving our environmental crisis. To build a future that fits within the Doughnut Economics model, we’ll need more than trendy alternatives. We need systems that support sustainable living for everyone, not just those who can afford the “organic” label. As the Doughnut Economics model reminds us, real progress lies in balancing our social foundation—where everyone’s needs are met—with the Earth’s limits. If sustainable choices remain exclusive, we miss the bigger picture: true sustainability isn’t just about eco-friendly products with leafy logos and green packaging, but about creating an economy where everyone has the means to live well and live lightly on the planet.

Featured image by The Printed Bag Shop.