About one-third of the reason I am doing a BIR degree can be traced back to Steve Rogers. I was 17, in my second-to-last year of high school, when Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) came out. I sat in the cinema in Singapore on opening night, dressed up as Bucky Barnes (fake metal arm included), as the film heel-kicked me in the sternum again and again. As both sociopolitical mirror and commentary; as a deeply thematic film about trust and identity and responsibility; and as a film helmed by a hero whose personality, values, and flaws resonated with me, it stuck with me for literal months afterward. And when it came time to start considering my future, it’s as simple as saying that Steve Rogers hitting back at the people in power for their categorical moral failure as leaders made me want to do that too.

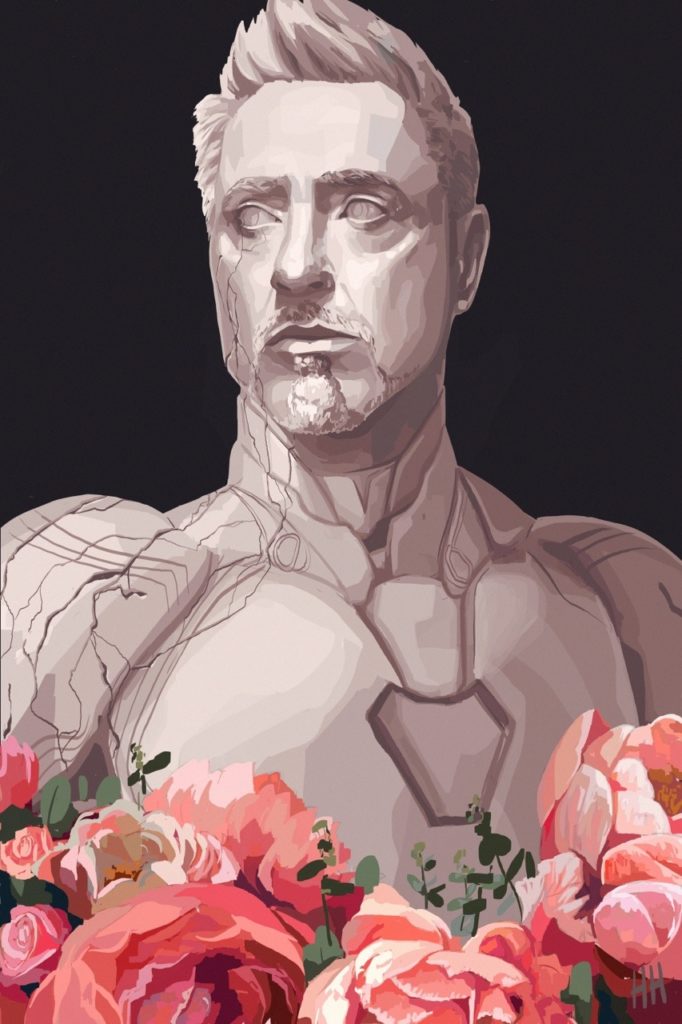

I am far from the only person to have resonated so deeply with an MCU film and character. Following the release of Avengers: Endgame (2019), fans around the world had deep and visceral reactions to the end of an epic story – and of some of our most beloved characters. This September, when IE students were getting stuck into their first week back, an Iron Man statue was erected in Italy as a tribute to the hero’s ultimate sacrifice in Endgame. If this is an example of anything, it is the tangible global impact these heroes have had, cementing themselves in our daily lives. It’s not just pop culture, or box office numbers, or the impact the MCU has had on film industries worldwide. IE student Azul Berruezo says that “the fact that Endgame is already the most profitable movie in history says it all…[these] characters have grown with many of us and that will be hard to substitute for another saga. I would even compare it to a modern Star Wars.”

So what is it about the MCU that hit us so deeply? It lies in how these past 22 films have depicted heroes and heroism, pulling triple duty in their construction. The films ground themselves upon eternal human themes of justice, power, responsibility, and the importance of our choices. They define their heroes as deeply flawed and relatable characters who have a lasting impact on their world. They root themselves very firmly in the salient issues of the 21st Century. These films carry the trappings of blockbuster cinema with their universal action and comedic appeal and yet transcend it with its meaningful personal storylines that touch people across countries and cultures. They’ve taken on a life of their own in society, entering our cities as statues, entering our class debates on sustainability when we argue if Thanos was right, entering our lives as we use their slogans to motivate ourselves (I doubt I’m the only one who tells myself “I can do this all day” when the going gets tough). As Lupita Prada, a 5th-year LLB-BIR student, says, “Superheroes are like royalty, we know they are there but we can’t be like them, we can only admire them and aspire to be like them. And this I think is a good thing, admiration is a great human value, and the MCU inspires that in its audience.”

If the statue is anything to go by, Tony Stark is easily the most admired and most beloved MCU character. As the “godfather” of the MCU, he presented the world with a hero that had deep rifts within himself and the world around him – “spiritually dead”, in the words of Robert Downey, Jr. – and underwent a transformative journey that turned his power from harm to heroism. He stands as the prime example of Marvel’s particular brand of heroism, rooted in “emotion, angst, and humour”. The stories of Steve Rogers, Natasha Romanoff, Thor, Clint Barton, Bruce Banner, and all the other later heroes are based on individual and group choices, failure, redemption, survival, growth, and personal sacrifice hung on a frame of the greater struggle between darkness and light, interconnected by their relationships and given plenty of levity to get us through the fight. Berruezo reflects, “We should always pursue what we think is right and stay loyal to our values even if that means sacrifices.” And indeed, as is common in a lot of media – particularly that which comes out of the U.S. – sacrifice is a cornerstone of heroism. There is a reason that the track “The Real Hero” on the Endgame official soundtrack is the one that plays during Tony Stark’s funeral. One can debate about how meaningful certain sacrifices of certain heroes were, especially in Endgame, but the point stands that the most difficult choices make heroes of humans.

In the end, it cements one core principle driving the MCU’s creation of mythology: these heroes are not their accomplishments – they are their choices. In-universe, the perception they take on in society does not always reflect who they are, and this is as meta an example of heroism as can be found. Steve Rogers was made into the symbol of America – does that mean he’ll obey the Sokovia Accords in Captain America: Civil War (2016)? No – because Captain America is not Steve Rogers. It enables us to see ourselves in people who are larger than life, and equally criticize and take our cues from them. We resonate with the inner world of a person and are moved and challenged by the presentation of their outer world. The MCU is a fully realized universe of a story where these characters take a stand on their principles and change the world – for better, mostly, but sometimes for worse. Prada finds this to be one of the main areas of appeal for the MCU: “their heroes are diverse, are in some sense ‘real’. I think every character is well developed, and each of them has their own story, their own personality”. Heroes don’t last because they are perfect. Nobody remembers Achilles because he was a fine, upstanding Achaean. They remember him because of his fate, his feuds, and his famous rage that had him dragging Hector in the dirt behind his chariot.

While the MCU heroes are somewhat less tragic, they too wrestle with difficult and conflicting aspects of themselves, whether obvious in the duality of Bruce Banner versus The Hulk, or resting deeper beneath the skin in Steve Rogers’ nobility that belies his dangerous arrogance. In this latter sense, the MCU also created a new way to tell the superhero story. Marvel has never been afraid to play these characters’ flaws against each other for all they’re worth. The Avengers (2012) worked because the characters had these fully realized histories and personalities and they were able to play off each other to create a deep interpersonal conflict underneath the banner of the greater threat they needed to unite against. Working through these differences and learning to manage them enabled them to become the heroes they must be, and that is something that humanizes heroes that would otherwise be as distant as gods. And as such interpersonal conflicts would play out in real life, Marvel had the guts to take these differences to their logical conclusion in Captain America: Civil War and end with their characters split almost irreconcilably – until Endgame, of course.

Part of the MCU’s success is its ability to thread these interpersonal struggles as the core thematic throughlines across the films. Compare the thematic questions of freedom versus protection, selfishness versus selflessness, the future versus the present, and the individual versus the collective good. They can be tracked across the cinematic universe, initially emerging in the first argument between Tony Stark and Steve Rogers in The Avengers. When we get to Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), the conflict has deepened to the point that it goes on to form virtually the entirety of Civil War. When it makes its last appearance in Endgame, the thematic and emotional gravitas hits hard. Beneath these throughlines are deeply personal investments from both characters and their longstanding individual histories. They all have a stake in the conflict and ought to work together but cannot exist independent of the people they are, and this is what defines how their heroic personas manifest. It proves that heroes can be wrong. And it proves that arguments that may have been right in the past, are proved wrong by the future.

The MCU has been able to broaden the scope of these tales and both the human and heroic aspects of these characters through their unique format of serialized storytelling in films, creating more – and different – opportunities for conflict that can be explored. “[C]onflict breeds catastrophe,” or so says The Vision in Civil War, but it also provides an opportunity for our beloved characters to continually evolve and continue to sculpt an image of heroism. Mythology does not exist in a vacuum, and the heroes always come down to earth. Mythology is as much a reflection of our world as it is a response to the challenges it poses. This is why we tell myths. We have a full framework to understand our world. The MCU has taken that to another extreme because the mythology is independent of culture. It operates on a scale of the global zeitgeist – rooted in its American origin, yes, but proven to be wholly international in the kind of fanbase it has engendered from Seoul to San Francisco to Spain to South Africa. Italy has a statue. Malaysia had a lights show. Every nation had some sort of comic con, some sort of marathon screening of the films. It went beyond pop culture to an everyday integration into our society.

So what is the MCU’s position as a reflection or response to our broader society? Berruezo believes that the films have grown as a response to how they address these themes. “At first they took place without much care about political or social movements,” she says, “but I think it’s possible to appreciate how they have changed with new narratives and characters as time goes by and activism becomes relevant.” One might contend that this is true in that the films have fluctuated in how they are driven or impacted by our social milieu. Was Black Panther (2018), for example, a reflection of our changing attitudes towards diverse representation in mainstream media, or a response to the call for this from stakeholders – and by stakeholders, I’m referring to the MCU’s global, diverse audience? The argument could be made for both sides.

The other obvious case is The Winter Soldier, with its release at the height of the Syrian Civil War and the propagation of U.S. drone strikes in combat there, and just a year after the NSA leaks by Snowden. These contemporary issues were reflected in its commentary on freedom, fear, security, and the ethics of decision making for the greater good. Yet when Steve Rogers actively decided to act against Project Insight alongside his companions, including individuals who made on the spot decisions not to comply with morally questionable orders, it transformed into a response. When our heroes take a stand for their values, they become icons and arguments, giving people in the real world a particular beacon to turn towards and guide their own proactive actions in response to their local and global milieu. Berruezo feels that “these 11 years have been very interesting to observe how artistic expressions such as cinema can adapt to suit the needs of a new society that rapidly changes.”

When I finally saw Avengers: Endgame, during my exchange in Moscow, I realized two distinct things: this was the end of a cinematic era and the beginning of a new social one. It offered closure as well as a way forward. As an individual, I had grown up along with my heroes, and their failures and triumphs had become as much a part of my journey as theirs. I was sad to say goodbye, and yet the lessons they had learned over the years as part of their journeys, they had imparted to me. As a fan, I felt the inclusive, broad reach of the stories that united me with so many other people from all over the world. This, I think, is the final cornerstone of the mythology – its universal, intergenerational, intercultural framework. Berruezo felt the same: “The fan community was definitely it, to feel part of a broad group of people and share the excitement for something is one of the parts that I enjoyed the most about the movies. But also the characters, not because they are extraordinarily built (although their development is good) also because I have grown up with them.” The MCU may not have created a suit of armor around the world, but it created a common framework for heroism, stories, and people, that has had an indelible effect on the way I and many others see the world and live our lives.

Through their characters and storytelling, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has created modern mythology of heroes defined by – and continues to define – our global society. From my personal journey through to the journeys of others, expressed in art and word and music and community, it becomes apparent that Marvel heroes have grown beyond film into a cultural phenomenon both responding and contributing to our global sociopolitical zeitgeist. Heroes are not an old-fashioned notion. We choose our heroes. They evolve with us and become part of us and manifest in media and monuments and slogans that echo in the world around us. A mythos was created and heroes raised into the global social consciousness whose stories we can go back to and draw inspiration and hope from as we move forward into our strange and often bewildering future. So it was in antiquity, and so it is in the 21st century. One could say it was inevitable – if heroes did not live to rail against inevitability.