First and foremost, a gift is never free.

Imagine that it is your birthday, your friends have planned an outing for you at a restaurant. At the table you begin to unwrap the presents that were brought for you. One of your friends in particular has given you a beautiful silver piece: artisan earrings that you cannot get in a regular chain jewelry store. In that moment, a wave of gratitude and appreciation of your friendship washes over you. However, flash forward to the day of that friend’s birthday, the need to find a birthday gift that was just as touching as the one you received grips you strongly and you begin to search and tear through all the stores in Puerta de Sol to find the perfect present. Why must simply buying a birthday gift feel like an obligation? Although you are volunteering to buy the gift, why does the act of ‘giving’ feel more like a commitment sometimes? That is because no gift is ever truly free, and those gifts that are given in return must be similar to those received.

The purpose of this example was to not dampen the approaching birthday of your friend but rather to illustrate that it is hardly ever a simple act of giving a gift as well as receiving. This phenomenon is called gift exchange and is a core topic of study within the field of anthropology. But how exactly does this knowledge help you? Well, it can bring you greater awareness to navigate the social world that you step into each day. It is even possible, you may come to the understanding that gifts are obligatory and the need to reciprocate is very real.

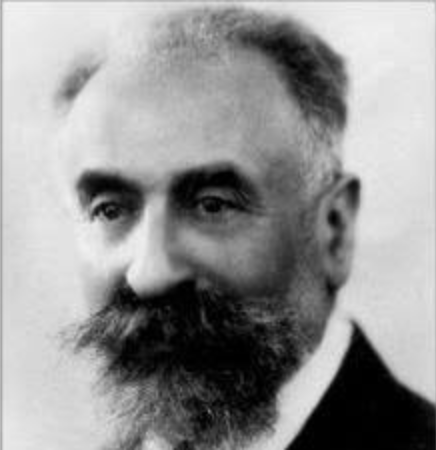

Marcel Mauss, a French sociologist, published an anthropological essay called ‘The Gift’ in 1925. Mauss’ work is considered absolutely groundbreaking, he developed the foundations for understanding the institution of gifts and its role within the system of exchange. In his work, Mauss considered the gift not as a simple commodity but rather is part of an entire social process in which several basic notions exist. Consider, there is an obligation to give a gift, an obligation to receive and an obligation to return the gift. When your friend gave you the birthday gift, you may have considered them to be generous, thoughtful and deserving of your friendship. And in receiving the gift you felt obliged to accept it and in doing so you show respect to the giver. Finally, the need to return the gift and it’s actual giving establishes that your honour is equal to that of your friend. These commitments are connected directly to morality, and in conducting this exchange it establishes a moral bond between yourself and your friend.

In some scenarios, we can go as far as saying that by giving your friend a better gift or even more gifts you are at a greater position in terms of the respect that is owed to you. For example, Marcel Mauss primarily emphasized the competitiveness of gift giving in his ethnographic description of the potlatch. The term ‘potlatch’ is originally a gift giving ceremony which was held by the Native Americans of the Northwest Pacific coast. This ceremony consists of a formal display of wealth which aims to reaffirm the social status of a new heir or successor. During this ceremony, different activities take place such as speech giving, a great feast and most importantly the distribution of goods to the invited guests by it’s esteemed donor. In other words, the bigger the ceremony and the greater the gifts, the higher social status the host of the potlatch gains. By such a great display of goods and hospitality, the host reinstates his place within the hierarchy of his kin.

Ceremonial Masks used during the Potlatch

However, this archaic ceremony can come off as far removed from our modern lives and even the idea of gift competitiveness may seem arbitrary. But this is not necessarily the case.

So, where can we see examples of gift giving within our own lives? For those who have befriended a peer during elementary school whose parents were quite wealthy, you may remember that attending that friend’s birthday party was quite the treat. At a child’s birthday party it is usually customary to give your guests a ‘goody bag’ at the end of the party when you leave. In this bag can be a different rage of objects such as candy or small plastic toys. And during a birthday party like this it is possible that as a guest you could receive a goody bag that is even more expensive than the gift you brought. If this is the case for each year, then it would not matter what gift you brought, it was likely that the goody bag outranked whatever you had given. Like the potlatch, the generous and most gracious host is who gains the highest social status between their kin. Although the aim of your friend’s parents was not necessarily to out compete the guests but rather to express their gratitude. At the same time, if one was to go to this same birthday party each year, and each time your gift is outranked by the goody bag, why would you even try to give a birthday gift anymore? The host has maintained a social status high enough in which he is inclined to give but not to receive. Each birthday party for their child is a display of wealth but also sharing part of it with their friends which helps to maintain these relationships.

To come to a conclusion, let us discuss the concept of gift giving applied within a classroom setting.

So, why should you never accept a muffin (or any type of pastry) from your professor? Is it possible that your professor has an underlying directive in offering you food? If you are sitting in an anthropology class, it is likely the professor has a full comprehension of what they are doing by offering. Even if the full awareness is not there, most teachers understand the result of giving a gift to their students. And because a gift is never truly free, the professor will expect some type of social reciprocity from you. In accepting the muffin from your anthropology teacher, it is expected of you to give your continued and maybe even greater respect. Although you are not being obliged to, you most likely are motivated to make small changes in your behavior. You are likely to install a greater respect for that professor or feel less inclined to talk to your friend during class, as someone with a greater social status has laden you with their recognition.

In general, a gift is an object that can be moved strategically through the social world and aids in your navigation and understanding of it. With the gift you are able to rearrange social relationships and hierarchies as well establish some form of status among your kin and friends. The gift contains a power that stretches across so many institutions of society, whether it be religious, political, personal or social.

“One must be a friend

To one’s friend,

And give present for present;

One must have

Laughter for laughter

And sorrow for lies”

Havamal, The Words of Odin, The Great One