The dominance of written traditions and the preference for formal academic discourse has long prevailed in the academic sphere. Although writing is not the ultimate supreme way to divulge information, it has been the dominant perspective in the Western world. The academic world is full of many more methods which are deeply entrenched in historical and cultural pasts. In many other regions across the globe, oral traditions take center stage. It is important that this hierarchy of written over oral traditions is questioned because oral expression has incredible value and must be recognized as an equal in the academic world. If we are only emphasizing written tradition as the best mode for knowledge transfer, then oral-centric cultures get sidelined. This can result in people from areas with rich oral histories viewing their cultural contributions as less valuable or even less valid in these academic spaces.

Oral traditions involve the sharing of knowledge, culture, and history through spoken word, often through poems, proverbs, and stories. Written traditions, in contrast, favor documentation and preservation of information through writing. The nature of this approach makes stories, such as myths and legends, less adaptable and more permanent. The reliance on memory and verbal communication makes oral traditions distinct. Consciously emphasizing the value of integrating oral traditions can make an academic space more enriched and holistic. Highlighting activities like storytelling events or oral history projects are great initiatives that can create a welcoming space for all sorts of cultural backgrounds. Acknowledging the value of oral traditions allows us to focus on discussions where we emphasize the value of synthesizing oral and written traditions as equals.

It is important for us to acknowledge that oral and written traditions should not be viewed as binaries because they are interconnected modes of cultural expression.

As we discuss what these two traditions look like, it is very easy to view them as binaries or, at the very least, opposite ends of a spectrum. This is the very problem at hand. Oral and written traditions aren’t completely independent; they largely interact with and shape one another. Oral traditions can influence written texts, and written traditions can serve as a way of formalizing oral traditions. In fact, when we study oral traditions, we are often looking at how they interact with written culture. For example, we see how oral narratives are documented, showing the interplay between the two forms. The categorization of oral and written traditions as binaries has deep historical roots, often influenced by colonial perspectives. Some argue that assuming written knowledge is inherently more reliable or valuable reinforces this binary and overlooks the adaptability and depth of oral traditions. Additionally, others argue that replacing oral tradition with written records is a form of cultural colonialism because it takes away from the unique traits and social functions of oral traditions.

Oral traditions have so much to offer and are widely recognized as more diverse in content and social function than written traditions. Despite enjoying and even appreciating oral contributions to culture like myths, songs, and riddles, oral traditions are still not viewed as equally sophisticated as written ones. This is partly because they are relatively more accessible to any given person than written tradition in the Western world. However, oral traditions are sophisticated in their own way: they demand complex structures, have high cultural significance, and adapt across generations. In acting as repositories of knowledge, these traditions also give us insights into societal norms through metaphors and the structures that they use. This dominance of largely Western written scholarship has resulted in the marginalization of oral traditions, even in the study of non-Western literary works. For instance, indigenous and African communities have long used storytelling to preserve knowledge, yet these oral traditions are often dismissed as informal in academia. This bias marginalizes certain voices, upholding a Western-centric view of knowledge and reinforces a hierarchy that marks oral-centric cultures as ‘less developed.‘ Such marginalization can poorly affect the cultural representation of students from these traditions.

Oral traditions have proven that even without a formal text, valuable information can still be transmitted across generations, underscoring their value. The Western perspective of oral traditions in relation to written traditions has changed over time. Historically, this has looked like coming up with approaches to validate oral traditions as historical sources. However, some critique this approach, arguing that it imposes Western standards for communication on information from other cultures. Reflecting on instances like these can encourage individuals to consider how this bias, seen in the preference for written over oral knowledge, affects their learning environment.

It is important for us to acknowledge that oral and written traditions should not be viewed as binaries because they are interconnected modes of cultural expression. Both contribute to our understanding of cultural heritage and history. Viewing oral traditions as somehow opposite to or “less than” written traditions limits our understanding. Valuing both these types of knowledge allows for a more inclusive academic environment. As you continue to interact with a range of cultures within the academic space, ask yourself if the information you’re consuming propels us toward a syncretic and considerate space or keeps us stuck. Oral traditions’ strengths in adaptability and memory recall illustrate that they are not only valuable but essential in academic settings. The shift toward recognizing and preserving oral traditions alongside written ones represents an important step toward a more inclusive and culturally aware academic space. This emphasis on inclusivity will enrich our understanding of human culture and ensure that diverse methods of expression are honored equally.

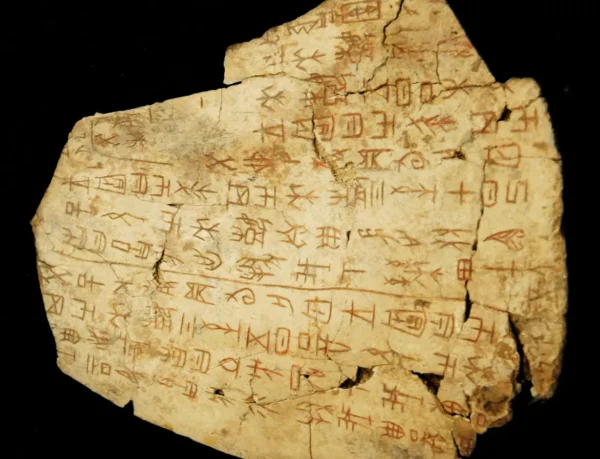

Featured image provided by Amrita Sher-Gil, titled Ancient Storyteller, first published in 1940.