We walked into Museo del Prado at half past 6, free entry time—Gabriel, Elvis, and I, standing in a long cue, chitchatting and marveling at the immaculate view of El Prado’s lobby. Elvis, a former Kistefos Scholar at IE University, flew into Madrid from the annual Kistefos Alumni meeting in Oslo, Norway, and reconnected with Gabriel, his former classmate from the Masters in Management (MiM) at IE. I don’t know the chances that you would bump into someone you know from Liberia in this big city, some extremely unlikely odd, but that’s what happened. Our journey to the Prado ushered me into a new phase of questions, curiosity, and imaginings – but long last, dreams fulfilled.

I come from a small country, Liberia, located along the West Coast of Africa and home to approximately 5 million people of various Indigenous and ethnic groups. Despite its rich history, little is shown in collections, museums, and storytelling (many conflicted histories). Every time I visited the Liberia National Museum, my spirit shrunk; there is so much vast space of untold stories and nothing to show for it despite how far our history goes and the many events that have shaped our development, culture, politics, and lifestyle as a people. I lived for more than two decades, longing to fill that space. I have taken it upon myself to organize two storytelling and arts-history events and over a dozen small gatherings and seminars in the past two years to encourage young people like myself to seek out and understand the various historical, cultural, and artistic contexts that shaped our society while cultivating learning at the same time. Many of my friends expressed that they had a great experience, but I didn’t feel it quite as much; I knew many things were missing still – things that I would encounter later in a different society – a perfect chord that binds and portrays who the Spanish people are, what stories they carry elemental to their existence, and how art has been and is still central to their lives.

Growing up, I fancied reading and studying the arts, but everything was abstract because there was little to grasp besides what I could access through various texts. I would spend long days in my school library reading about different artistic movements and how they influenced European societies – the Renaissance and how it reinvigorated life, spirit, and an appreciation for beauty while engendering the revival of arts, culture, and learning after the bubonic plague led to significant social and economic changes and a sharp reversal in livelihoods across Europe. Then, one day, I found myself standing before Rafael’s original work, La Sacra Familia, and it all dawned on me that dreams do come true. Gabriel asked me, “What do you see in this painting?” I didn’t know where to start – because I’d carried those dreams too long, and they all seemed farfetched until then. I was dumbfounded with shock and amazement simultaneously. Then we toured the Prado continuously, slow steps walking past centuries of history cast down upon us. Gabriel introduced us to El Greco, Sorolla, Velázquez, and Francisco de Goya, including Spanish masters such as José de Ribera and Francisco de Zurbarán. We spent minutes discussing Las Meninas and how it characterized Velazquez as a man, The Third of May 1808 in Madrid (1814), and many more.

We walked into the room housing Goya’s dark series, full of melodrama, moving with life, and it felt like there were ghosts from centuries past peering upon us. Morbid. Deep. Dark. Shadowy. And more than ever before, I tend to understand why paintings are so cherished, highly prized, and enduringly relevant because of the stories they show about a nation’s past, which is eternally present and alive for viewers.

When Elvis departed for Liberia, Gabriel and I completed the Trio, making trips to Reina Sofia and Museo Thyssen. We studied Cubism (the dominant theme reverberating throughout the Reina Sofia), surrealism, impressionism, and Modernism.

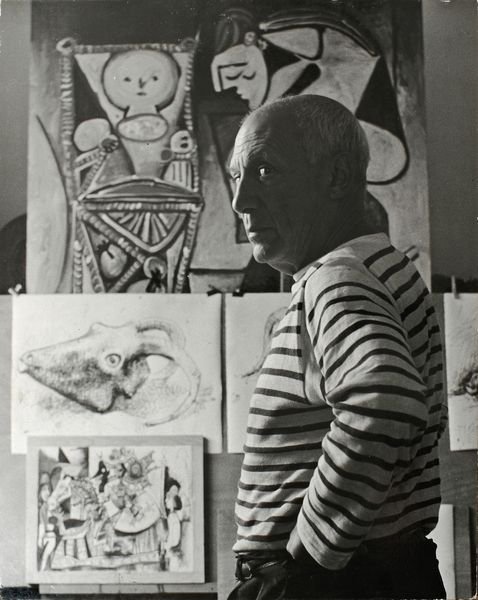

When we walked in, as usual, Gabriel wore a deeper voice, slightly cinematic, as the lead storyteller, and when he asked, “What did you see?” when we came upon the first Picasso’s work, I had words: cubes. Many cubic polygons arranged in different proportions. Disjointed but full of meaning from various perspectives – thus the artistic movement, Cubism. Even strikingly present and commanding so much power and attention in Guernica (a painting I still see at night when I close my eyes), perhaps Picasso’s most famous work.

Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and the French painter Georges Braque, ushered in a new style of painting in two proportions: Analytical Cubism, which focused on breaking down objects into geometric shapes, and Synthetic Cubism, which introduced collage elements and emphasized the use of color. It is said that Picasso first demonstrated this new style in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Braque in works such as Violin and Candlestick. But what was the underlying meaning of all this? Cubism focused on using fractured pieces to represent subjects abstractly and inspired thinking through various theoretical and philosophical frameworks before making judgments of the whole. We turned our heads in different directions to arrive at conclusions, trying to put all the pieces together from various angles. And this is essential in human reasoning and thought processes. How well one should think, and how limitless are the possibilities of perception.

Cubism even influenced writers like Ernest Hemingway in how they approached certain subjects. Earlier in his life, as a young journalist, fascinated by this new movement, Hemingway learned to pack meaning into a few words. This new style helped develop his writing identity, as he focused on minimalism, taking multiple storytelling angles. In the same way, that Cubism creates a canvas for the viewer’s imagination, Hemingway’s Iceberg theory leaves readers with much to unravel as they journey through his stories. Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” is a masterclass in the Iceberg Theory -an entire conversation about an impending abortion without the word ever being mentioned. The characters’ tension and despair bubble beneath the mundane dialogue’s surface. At its core, the Iceberg Theory is show, don’t tell. Let readers infer the meaning behind the scene and character by giving as little information as possible. As the story progresses, predictability reduces the need for explanations. So, what can modern societies and people learn from the iceberg theory? Or Cubism? Seeing things from multiple perspectives, thinking thoroughly, looking for the story untold, showing, and being willing to learn as much as possible from other perspectives.

Then we went on to view other works and focused on surrealism: how the artists tried to bring dreams and the unconscious mind to life in art, juxtaposing unexpected and abstract elements essential to our human existence. We discussed the emergence of surrealism and how it helped societies rethink things of the subconscious level of rationality and imagination. Sex became viewed and appreciated as an act of pleasure and not merely a process of procreation, something humans can make more of because we are separated from animals on a higher level of feeling, desire, emotions, and ecstasy.

Other themes, such as impressionism, characterized by loosed brush strokes creating a solid expression on canvas by emphasizing pockets of light and movement on familiar daily scenes, which brought up in our conversation how we too can touch the lives of others with gentle strokes – of kindness, love, service – and create lasting images. The impressionists’ works are not made of hard-pressed actions at once; they contain several layers and pieces of one-time touches. They are made of repetitive acts. We went on to experience much of the Romanticism periods and other eras, and finally, Modernism, acknowledging how much arts changed across times and ages, yet embodied the words of Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish Baroque painter, that “all art is but an imitation of nature, in her most beautiful, but also her most rational form, full of reason.”Throughout our journey to Triangulo del Arte, over a month, we encountered young painters who walked the mile there for inspiration and spent days trying to create a copy of artistic works on sheets and understand the details. We walked past travelers and wanderers from afar, lovers of all ages bringing so much love alive—violin music in the squares creating an ambiance of warmth. Curious onlookers stared so hard and deep to see unspoken themes.

Everything beautiful and poetic happens in that Triangle… so much of life. For a moment, you forget there’s a whole universe outside, beyond you – an imperfect world. You forget the wars in the Middle East and the poverty in Africa. You forget about all the melancholy and disdain of life, its sham and drudgery; everything grows infinitesimal compared to the permeating beauty and elegance of art that is loud and audible in this Triangle, overwhelming and bewildering you all at once. And for me, the absolute beauty and tragedy of the human experience became so visible, so touching, and so extraordinary – that we are capable of the worst atrocities and, simultaneously, the best and most beautiful and impactful acts of beauty. Every time we stood before those works, I imagined how it is that you’re both humbled and exalted— humbled by the sheer weight of all that past and beauty in whose presence you stand and exalted by the fact that you belong to the race capable of such past and such beauty, and more than that, even though you’re faced with the enormity of all the universe that exists outside you, you recognize your place in that same universe. That you are here. Now. IN the moment.

It was a pleasure to take you around these treasures in Madrid! I´m glad they opened your imagination, and it´s clear that your encounters with the great artworks housed in the “Triángulo del Arte” helped to expand you. This is what great art can do, and as readers of your article, we´re grateful for your carefully crafted and eloquent recounting of these visits!