Over 10,000 published research papers were recalled in 2023– a new record. From flipping and recycling images in older research to the classic p-hacking, where researchers manipulate statistical methods to achieve desired outcomes, misconduct is becoming more prevalent. Scientific misconduct is more than a frustration. It is an incredible threat. It threatens people’s ability to trust not only papers by that specific researcher but the field in general. Even one isolated instance of esteemed and highly-referenced research being proven false can take an irreversible hit to people’s trust in the credibility of research and the integrity of academic institutions. If that isn’t bad enough, countless individuals rely on advancements in scientific literature to make decisions regarding their health and well-being. While this can be frustrating for individuals with a mild recurring rash, it can escalate to life-threatening consequences for those with terminal illnesses.

It would be short-sighted to frame this fraudulence as malicious. There’s incredible pressure to continually put out more literature, with a preference for topics that are novel, further increasing the incentive for people to cut corners. Universities are a big stakeholder in this dilemma and it is crucial for them to reflect on how they can positively contribute to resolving this problem. Current students who may be future researchers can then be equipped with the knowledge and the tools to create a more trustworthy environment for academia.

In these academic settings we are, of course, told to be wary of the sources we use and favour academic sources over more opinionated mediums like YouTube videos and blog posts. This is incredibly logical as science does its best to be objective, as well as reliable, replicable, and valid. However, when we categorise sources of information into binaries like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ (with academic literature being the ‘good’ box), it leaves us little room to question the integrity of academic literature in itself. This is especially concerning in cases where the course isn’t focused on evaluating and crafting academic literature. In instances where you simply have to submit a paper as part of your assignments, students may not even consider verifying the quality of that academic source in question. Universities could be doing much more to provide comprehensive sessions which allow students to navigate these complexities. If students aren’t properly informed, there is a higher chance that they will be susceptible to the same misconduct. This comes at a disadvantage for both students and the academic institution which they represent.

In this discussion, the topic of reputation is undeniably important. Having a good reputation as a university will attract students and having a good reputation as a researcher will attract opportunities. There is pressure to maintain a good image even if it comes at the cost of integrity and research. It is not in an institution’s best interest to consistently criticise and nitpick seemingly successful literature affiliated with them, for if it is found to be fraudulent it would be devastating. While institutions will review output when a concrete concern is raised, it is still preferable for them to avoid such situations entirely. Being shunned publicly can lead to a loss of funding, and, of course, irreversibly tarnish the name of the institution as well as the individual involved.

This leads us to another big dilemma: the issue of replicability. What has happened on several occasions is that the numbers look entirely fine when peer reviewed. However, when other researchers go on to try and replicate the research, it all falls apart. The larger problem is that there is no incentive to carry out replication as a means of verifying the validity of the initial research. Many journals will even reject replications of the exact same research published in their journal. Furthermore, novelty is highly praised amongst researchers and replication is the exact opposite of that. In some ways you can call it a necessary evil.

All university programs where students are expected to conduct research at any point in their career within the field that they are studying should be mandated to participate in an ethics program that educates them on this issue. Having this ethics program spread out over several years can also serve to reinforce the idea of ethical principles at different stages of their education.

Considering that several millions of papers are published annually, 10,000 recalled papers does seem minuscule initially. Yet, when you consider the fact that not all the fraudulent papers are caught and that the average person probably wouldn’t read more than five scientific papers to form an opinion, then the weight of 10,000 fraudulent papers becomes much more tangible.

So how can we resolve scientific misconduct when there’s no incentive amongst the majority of researchers to do so? This is where university students come in handy. Undergraduate students, in particular, can be great people to execute these replicated studies. This is because, firstly, there is not a lot at stake. There is no real pressure to replicate, so they can take their time while still utilising guidance from professors and learning from their peers. There are countless students graduating with bachelor’s degrees all across the world annually, far more than people getting doctorates. This gives us a larger pool of potential researchers to work with. The best teacher is experience, and students having to conduct their own research can also help them appreciate the value of integrity. The hope is that because they won’t have the mounting pressure from their institution and coworkers, they will be able to replicate valuable research with little to no incentive to cut corners.

The combination of factors like the pressure to constantly publish literature, and the low incentive to address fraudulent studies is a persistent threat to the integrity of research. Despite this, we have the power to shift the landscape for the better by equipping individuals, namely students, with the right knowledge and empowering them to make right choices. In hopes that we can appreciate that research does not mean that we are to forcefully prove something to be true, but rather seeing research as a process of exploring how true it may be, and accept the complexity and sometimes inconsistent nature of research findings.

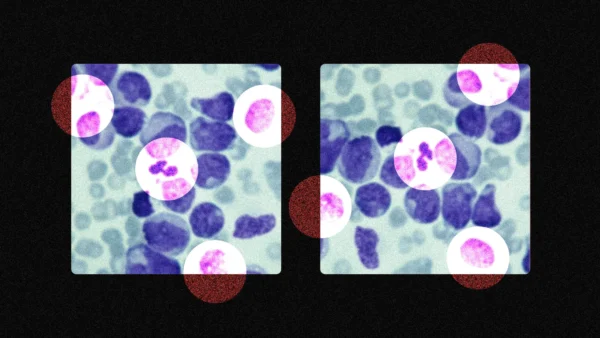

Featured image by Greg Pease, The New Yorker.