Imagine walking into a bookstore, perusing the aisles and taking in the aroma of ink and fresh paper as it fills the air. You caress the spines of the books on the shelves and run your fingers through their pages, appreciating their weight in your hands. Compared to its digital version, the tactile sensation of holding a book, flipping its pages, and even the act of placing it on a bookshelf offers a more memorable and emotionally fulfilling experience than any Kindle or e-book ever could.

A Pew Research Centre study from 2023 found that 77% of American adults prefer reading physical books to e-books, citing emotional and sensory aspects as significant factors. This preference for the tactile sensation of a physical book over its digital counterpart serves as an example of our predisposition towards material things in any and every aspect of our lives – even if we don’t fully realise it, given how immersed we are in the digital age.

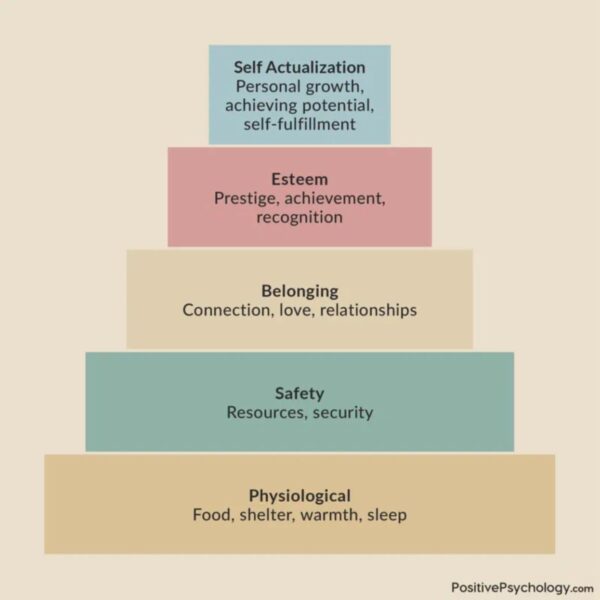

Humans have an innate preference for tangible objects and experiences, deeply rooted in our biology. The sense of touch is fundamental to how we understand and navigate our surroundings, as our sensory system is designed to interact with the physical world. The biological reliance on the sense of touch is evident from infancy, where it plays a critical role in bonding and cognitive development. Even as adults, physical interactions with which we engage with our environment activate neural pathways that positively contribute to our emotional well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs places physiological needs at the forefront of our essential necessities. Touch, once indispensable for the hunter-gatherer survival, now plays a detrimental role in shaping our neural architecture and emotional grounding today.

Apart from the inherent physical necessities that relyon touch, we find significant psychological comfort in physical interactions and activities. It is no mystery that sensory experiences, including our hobbies (e.g. crafting, playing an instrument or collecting objects) provide a feeling of satisfaction, which explains why we still gravitate towards these activities in the digital age. Physical items, such as books, pictures, or souvenirs, offer a tangible depiction of memories and identity. These artefacts anchor us emotionally and operate as markers of permanence in a world where digital files and online interactions often feel ephemeral and transient. Psychologically, humans find comfort and stability in engaging with physical objects, as they offer a sense of control and permanence that digital experiences lack.

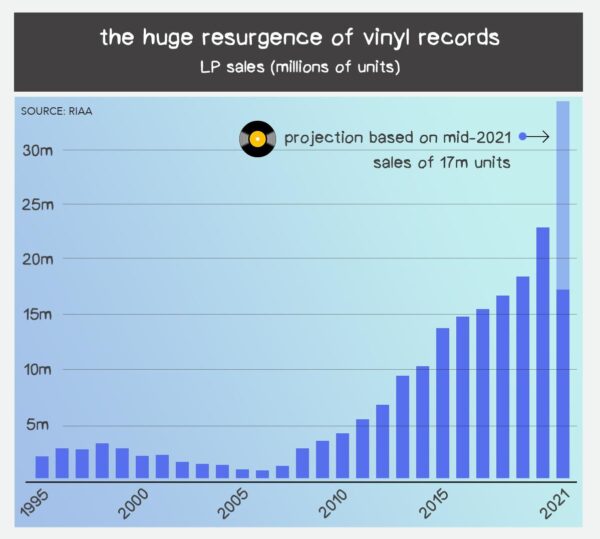

Another example of this trend is the recent rise in vinyl record sales. For many music fans, vinyl offers not only a tactile way of experiencing music that they love but also a nostalgic journey to a previous era. Tapping the play button on Spotify lacks the immersive interaction of holding a record, carefully positioning the needle, and listening to analogue music. According to the RIAA, LP sales in the first half of 2019 increased by 13% to $224 million. During the entire year of 2019, they surpassed CDs for the first time since 1986, reaching $500 million. Physical media is indeed making a comeback, which is a manifestation of a broader social shift, where people crave more tangible experiences that provide emotional depth and sensory richness, despite the occasionally high price tag. Similarly, swiping on your Kindle lacks the tactile pleasure of flipping pages in a book, annotating or writing on paper, which fosters a deeper cognitive and emotional connection.

The rise of digital platforms leaves users overwhelmed, flooded with intangible data, leading to what some psychologists describe as “digital fatigue”. In this context, the desire for tangible, physical experiences has grown as a counterbalance to the abstraction of the digital world. Reaching its hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic, “digital fatigue” became a widespread phenomenon as people were suddenly and inevitably spending unprecedented amounts of time interacting through screens for work and socialisation. This overreliance on digital platforms (e.g. zoom and social media) resulted in exhaustion and ,ironically, disconnection. While digital connections are in theory beneficial, they frequently left individuals feeling isolated, even though they were more “connected” than ever before. The involuntary loss of face-to-face experiences contributed to mental drain and social isolation, driving the exponential rise in demand for analogue versions of interactions and experiences across all aspects of life.

All things considered, it is not surprising why many young people are giving up on social media platforms – I’ve been dumbfounded by the number of friends closing their Instagram accounts – but, more importantly, turning away from dating apps. Apart from their free-time activities, the need for tangible connection has seeped into their dating views, and that is truly a need that no Tinder or Hinge can fulfil. The physical experience of dating – meeting someone at a bar, a cafe, or even at work or school – was stalled due to the oversimplified, algorithmic matchmaking of online dating. Yet, despite its convenience, digital dating could never completely replace the beauty of in-person connections.

In conclusion, while the digital world offers us the ability to stream infinite music, store thousands of photos, swipe through matches, and message friends without lifting more than a finger, it turns out we still like to feel things—quite literally. It is, in a sense, the universe’s subtle reminder that, despite the ease with which we can accomplish tasks these days, there is a profound and undeniable satisfaction in a real and well-executed touch. No matter how advanced and alluring our digital tools become, we’ll always gravitate towards the real and the physical, because deep down, we are analog creatures living in a digital world.

Featured image by: Pedro Pardo via Wikimedia Commons