A discussion on history, politics, and the opinions of IE students

On March 16, French President Emmanuel Macron invoked a special constitutional power to increase the pension age from 62 to 64 years old in France. Such special power is granted by article 49.3 of the French constitution, which allows a government to introduce a bill without a vote of the National Assembly, the lower house of the French parliament. By invoking this article, President Macron was able to sidestep parliament without requiring its approval. As Macron does not have an absolute majority in the National Assembly, resorting to special powers was the only manner in which this plan could persist.

While to outsiders it seems alienating to think of such special powers being used, it is not by far the first time, nor the last time, that article 49.3 will be applied. Since 1958, the article has been used 100 times, and Macron’s government itself has already utilized it multiple times to implement budgetary changes.

France has amongst the lowest retirement age in Europe, and given its aging population, the pension system would likely collapse if no reforms are implemented. As such, Macron’s intention to raise the pension age seems like a necessary, even if unpopular, plan. Given that Macron’s government withstood the resulting vote of no confidence, it is not only a necessary and unpopular one, but one that is likely to see realization. On April 14, the constitutional court of France approved the major elements of Macron’s pension reform. As such, the government has 15 days to enact the bill.

Nonetheless, since the start of February, when the bill was just announced and not yet imposed through the special constitutional powers, the French population reacted, and that they did with an intensity that had not been witnessed in over 50 years. The biggest protests since 1968 swept through France, and they have not stopped even two months later. Photographs and videos of thousands of people protesting, shouting, and singing on the streets, burning bins and people fleeing the police have spread through the news and social media. Sector-wide strikes are occurring parallelly, creating significant disruptions, especially in transport and health services.

Given the frequency of nationwide protests and strikes in recent years (let us just remember the Yellow Vests movement in 2018), Europeans often joke that “the French just like to protest.” Of course, having to work more years to gain a full pension is not a proposal that can be expected to be met with open arms. However, it is unlikely that the same proposal would have thrown another European nation into a similar state of anger and chaos. While it is a silly comment to make, some French IE students, like a fourth-year BBABIR student, agree that there is “a very reactionary spirit in France.”

It does raise interesting questions: why does France witness so many protests? And what is it about the pension age that strikes such a strong chord among the French population?

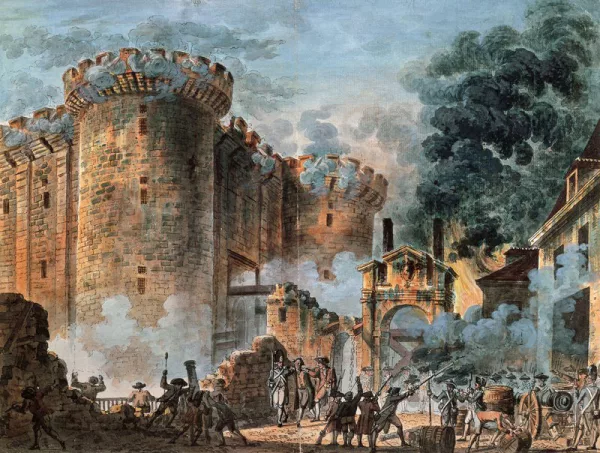

In discussing the roots of these protests, we first need to delve into the past, looking into what shaped the values of France and its democracy. The French Revolution of 1789 caused the destruction of France’s monarchical system. Ordinary men and women successfully stormed the Bastille, a symbol of public suppression, and portrayed the power that like-minded subjects of the monarchy can have. In line with the message promulgated during this Age of Enlightenment, the French were able to overcome a tyrant monarch and establish a new system of government based on the values of “liberté, egalité and fraternité” (liberty, equality, and fraternity).

It is clear that these values are what still fuels the French mentality today. As explained by a French fourth-year BBALLB student, “France as a country is based on democracy and the citizens being the sovereigns”. The ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity are severely undermined by invoking special constitutional powers that allow the government to bypass a vote on the pension age plan, and hence circumvent the opinion of those democratically elected by the people. As such, the decision to raise the pension age through special powers is one that is “entirely against the values France was created by” as put by the student.

It does not represent a necessary reform, but one that broke the social contract between the state and its people. “The inherent concept of democracy in France is more about social equality and social welfare”, a fourth-year PLELLB student who lived in France, explains. “Once you touch that, it is seen as an attack on democracy in itself.” With this in mind, the mass mobilization and discontent may seem more understandable to non-French citizens.

Apart from France’s history, the students pointed out that the French protests are not solely against the increase of the retirement age, but an emanation of discontent with Macron and his government. In the words of a French fourth-year BIR student, “Macron is the symbol of the new elite: young, liberal, and coming from the private sector to shake the political traditional landscape”. Since Macron’s election as President in 2017, he has come under attack for embodying the bourgeoisie, and the announcement of his retirement age plan fuelled the fire. It is claimed that his proposal will mainly affect low- and middle-income workers, aiding the sentiment that Macron has lost touch with his people. Another student explained that given France’s history, many people therefore “still view society through the lens of the battle of classes”.

The popular discontent with Macron was already visible during the 2022 presidential election, where Macron narrowly won against candidate Le Pen from the far right with just under 59% of the votes. Similarly, it represents the decline of traditional parties, where traditionally right-wing and left-wing parties collectively only generated 10% of the popular vote in the first round of the presidential elections.

As such, France’s political landscape is currently defined by an upsoar of anti-establishment sentiments and disillusionment with traditional parties and the current government. The retirement age plan seems to mark the last straw that brought the French population to erupt and voice their discontent.

When asked whether they agree with the current public outrage in France, most IE students shared similar sentiments: the negative feelings towards the usage of the special powers and towards Macron are understandable, however, the social reform is a necessary one. As a PLLELLB student puts it, “The current system is clearly not sustainable”.

Similarly, the students believe that it is unlikely that the protests will have a significant impact on preventing the implementation of the increase of the pension age. A third-year BIR student, summarized the situation after two months of protests well: “The country is in a stalemate with neither side willing to back down.” While the protests are still in full motion, another student suggests that it is likely that the protest may “exhaust itself” due to a lack of organization as seen with the Yellow Vest movement.

While French trade unions are currently showing a unified front and are the bond behind the protests, they are not as powerful as one may believe. There is no denying that these protests, largely organized by trade unions, have been able to mobilize over 1 million people across the nation. However, with just 9% of the workforce being members of trade unions, France has a lower number of trade union members than other large European Union countries. Compared to the Yellow Vests movement, they are a key player in the organization of the current protests. It is in the future that we will see if the unions will be able to maintain this influential position or whether the protests will die out. Given that the reform was consitutionally approved, it seems that public anger may now be the only element standing in the way of pension reform.

As such, it is visible that the current protests do not only symbolize discontent with the increased retirement age but represent a general anti-establishment movement within France. It is a protest against a government that bypassed a parliamentary vote and against a president that seems to have lost touch with the public. While the societal outrage may be underpinned by the values that the French democracy is based on, it is an expression of the significant polarization that exists in one of the most influential countries of the European Union.

Featured image: Fires lit amongst French protests against the pension reform in Paris, France. Photograph by James Hill for the New York Times.