When did the war in Myanmar start?

Last month?

Six months ago?

Three years ago?

Eight years ago?

10 years ago?

More?

For each person living in Myanmar, the conflict began on a different day.

Myanmar is no stranger to armed conflict. In 2010, Myanmar had its first civilian democratic government led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of a revolutionist and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate winner. That decade is known mostly for being the first decade of precarious peace within the country. Yet, she wasn’t entirely in control of it – the military junta still controlled some levels of power through the military-drafted Constitution.

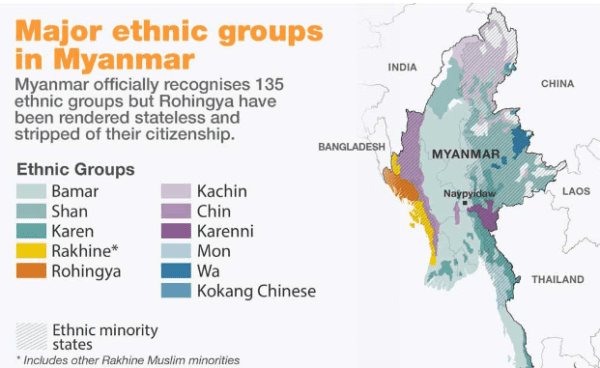

Because of this power, many others will associate the decade with violence and turmoil. Eight years ago, the military launched genocidal attacks directed against one of Myanmar’s ethnic populations, the Muslim Rohingya in the Rakhine State. Over a million have fled and 25 thousand have been killed. Most of Myanmar’s population are Buddhists, however, Myanmar officially recognizes 135 ethnic groups. This statistic does not include the Rohingya, who have been facing waves of ethnically motivated violence since the 1970s. Yet, amidst this, Suu Kyi defended General Hlaing, one of the prominent orchestrators of these attacks against accusations of genocide; in 2017 she noted that “she did not believe there were reports of ethnic violence.”

The 2021 military coup led by General Hliang and backed by the military toppled the former civilian government led by Suu Kyi, exacerbating divisions between the people. While Suu Kyi once symbolized hope for democracy, her tenure in power was marked by criticism, particularly regarding her response to the Rohingya crisis and her defense of General Hlaing. This tarnished her international reputation and eroded support for Myanmar, further complicating the narrative of the conflict.

Since then, major protests have emerged and been squashed by the regime, leading to the formation of rebellion and resistance groups. Simultaneously, waves of resistance against the military junta displayed a diverse coalition of forces joining together, including pro-democracy activists, civilians, and ethnic militias, taking up arms against the regime in indignation. Thousands have fled from the cities into the jungles for the fight. This convergence of disparate groups underscores the complex nature of this conflict, with grievances ranging from political oppression to ethnic discrimination. Several thousands of people have been killed, millions more have been displaced, and over half the population has gone into poverty.

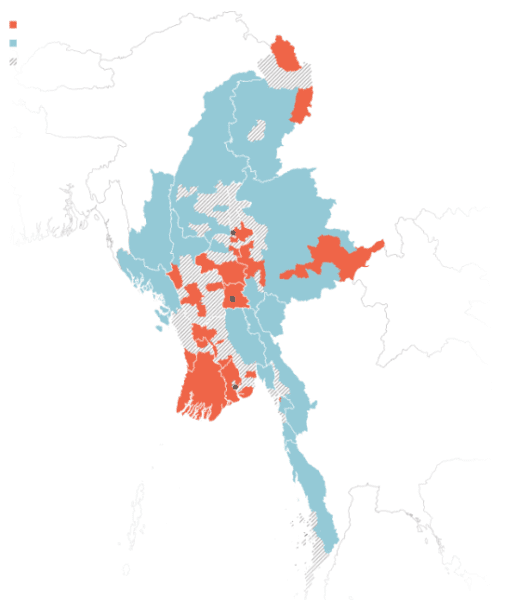

The regions colored in orange mean largely military junta control; blue is largely resistance control, while gray patterns are in contest.

Furthermore, the geographical spread of the fighting is significant within the country. Much of the focus has been on urban centers, especially in Yangon, where protests and crackdowns made headlines. Comparatively, rural areas and ethnic minority regions have and continue to bear the brunt of the violence. There, rebels have made significant gains in territories traditionally controlled by the military, posing a credible threat to the junta’s authority. More than half of the country has been freed from junta control. Control has been usurped by multiple resistance forces in small areas throughout the country. More recently, the intensification of the fighting in border towns has called for more international action. Because of the battles’ proximity to Thailand, the latter proposed an Association of Southeast Asian Nations, ASEAN meeting to discuss the ongoing conflict in Myanmar in fear of escalation between the junta and rebels, whom the junta is now calling terrorists.

Moreover, under the original 2021 Myanmar peace plan, the ASEAN chair had appointed a special envoy tasked with advancing the process and helping negotiate with both sides of the conflict. There is little public mention of the progress of the activities.

With the rebel fighters emerging more and more victorious, it raises the question of whether General Hlaing’s military junta regime is on the verge of collapse. And if so, what’s next for Myanmar?